Publishing is a slow machine. I sold my debut novel, Good People, to Simon & Schuster in March 2024, and it won’t come out until Summer 2026 at the earliest. This two-year delay happens in part because of the slow turnaround times for each step in the process. Right now, I’m in the long-haul wait for next steps after turning in my latest draft in February. Whether you’re querying, on submission to publishers, or waiting to hear back about developmental edits from your editor, the best thing to do while you wait is to start working on your next writing project. Now that I’m back from my trip abroad, it’s time for me to work on my option book.

What Is an Option Book?

When a writer signs a contract with a traditional publisher, the contract often includes something called a “right of first refusal” clause or an “option” clause. This provision essentially gives the publisher first “dibs” on your next book-length work. Now, an option clause is very different from a multi-book deal. A multi-book deal means that the publisher has acquired two or more books from an author, and these books are fully contracted and guaranteed to be published regardless of how well the first book performs. An option clause—on the other hand—only guarantees that the publisher will have an exclusive, non-competitive opportunity to consider the author’s next book for publication. This clause doesn’t guarantee that the publisher will acquire the option book. Publishing contracts generally state that the publisher has X days to review and consider the work for publication before the author and their agent are free to “take it wide” and submit the book to other publishers.

Sometimes, the option clause states that an author can submit a detailed proposal for their next book-length work. Other times, it states that the author is required to submit the full manuscript for consideration. Occasionally, even if the author has the full manuscript prepared, their agent might recommend submitting a proposal to test the waters. For me, since I’m in a long-haul wait anyway, I’m just going to go ahead and finish my next book. That said, my option book will be a page-one rewrite of You Will Survive This, my book that died on submission to publishers in 2023.

Novel Necromancy

Books die. Sometimes, they die because their writer loses interest in the story and moves onto a new project. Other times, they die because of the business of writing. When the business of writing is the cause of death, it’s usually because no agents offer representation during the querying process or no editors offer publishing deals during submission. So far in my career, I’ve written seven manuscripts—four in college/high school and three as an adult with a fully developed brain. Out of these seven books, my agent and I have put two of them on submission to publishers, but we only sold one of them. Four of these manuscripts are dead simply because I’ve grown as a writer and lost interest in their central questions. Writing these novels was absolutely necessary for my writing life because these books helped me discover my end-to-end writing process. But now as a professional writer, I see no reason to take them any further, and I keep them buried in the graveyard of my hard drive.

My two other books died because of the business of publishing. For Sub Club, I wrote about how it took five years for my agent and I to sell Good People and what those five years looked like on a craft and business level. The biggest hurdle for this book was the fact that Jo, the protagonist, was twenty years old and in the no man’s land between YA and adult fiction. We went on sub in August 2020. By the following April, my agent and I decided it was time to move on to the next book. At the time, I was weeks away from graduating with my MFA and I had recently finished a draft of my thesis novel as the final requirement for my degree. This book followed the story of a Black college student in Seoul who must help ghosts find peace before a reaper drags them to the underworld. Even though this book was far along in the writing process, it was an adult book with a twenty-year-old protagonist. I had to bury it in my hard drive’s graveyard because it would not be business savvy to submit another adult book with a twenty-year-old protagonist.

As a result, my agent and I decided to move on to You Will Survive This. We worked on YWST for the next two years1. By February 2023, I finished the book and we put it on sub. Despite having six solicitations from major publishers, YWST joined the other five manuscripts in the graveyard when it died on sub in 2023.

Now that I’m stuck in publishing purgatory as I wait for Good People’s next steps, I need to start working on my option book. My first step is to revive YWST from the graveyard for a page-one rewrite. I’m not gonna lie; I’m incredibly intimidated by the prospect of dismantling this book that I’ve already rewritten six times in the last four years. But my gut is urging me not to give up on this story just yet. Since I’m anxious about tackling this big rewrite, I’m going to do what I do best—break down this scary, seemingly insurmountable task into a manageable three-step process. If you have a dead (or shelved!) book that you’re ready to revive, here’s a three-step guide to novel necromancy.

How to Revive a Dead Book

Step 1: The Autopsy

Before we can revive a book, we have to understand why it died in the first place. In general, when it comes to revision, I’ve found that my writing sessions are more productive if I evaluate where I’ve been before deciding where to go next.

Here are three guiding questions to help you work through the “why” behind your book’s death:

Did you shelf the project for internal or external reasons?

Internal reasons are motivated by you and your own writing interests or habits. Some internal reasons include losing interest, getting a better idea, needing a break, or struggling with craft concepts or time management.

External reasons are motivated by someone outside of yourself. This “person” is usually a decent sample size of industry professionals such as agents and editors. External reasons include no interest after querying several agents or no publishing offers after submitting to several editors at various imprints.

If you shelved the project for internal reasons, what were the main things that were blocking your progress?

E.g. specific craft issues, your interest in the story’s subject matter, challenges with your writing process.

If you shelved the project because of feedback from industry professionals, what is some concrete feedback you received?

“I didn’t love the book enough” is a common pass that agents and editors will give in rejection letters, but it’s not concrete feedback. Concrete feedback typically focuses on craft issues like pacing or marketing issues like the YA/adult problem my book had.

Work to compile a list of solvable craft or marketing concerns.

Here are my answers for YWST. I’ll start with the pitch for context and then break down the book’s cause of death.

The Pitch for You Will Survive This

YOU WILL SURVIVE THIS follows the story of three people in a race to kill an immortal man.

Izzy, a Black researcher in Seoul, spends her days studying Korean folklore and isolating herself from the world around her. While touring an art museum, she meets Kim Taejong, a strange, wildly wealthy man who takes a special interest in her work. Taejong flies Izzy out to Jeju Island for a research trip, and they stumble across a woman from his past. In an act of violence, Blanche—a survivor of Taejong’s former cult—reveals his secret: he’s spent the last thousand years cursed with immortality. Back in Seoul, Izzy agrees to help Taejong find a cure for immortality using her folklore research. But when she finds something that might actually work, she must choose between spending her life with the man she loves and giving his long life a well-deserved end. Alternating between the perspectives of Izzy, Taejong, and Blanche, the story complicates as Taejong wants to find peace in a permanent death immediately, Izzy wants him to stay alive for the remainder of her lifetime, and Blanche wants to kill Taejong to take his eternal life for herself.

Using immortality as a lens to explore love, loss, and what it means to be alive, YOU WILL SURVIVE THIS has the magical realism of Jesmyn Ward’s SING, UNBURIED, SING, the dynamic setting of Frances Cha’s IF I HAD YOUR FACE, and the tone and style of Claire Vaye Watkins’s GOLD FAME CITRUS.

The Autopsy for You Will Survive This

1. Did you shelf the project for internal or external reasons?

External reasons. No offers after putting the novel on submission.

2. If you shelved the project because of feedback from industry professionals, what is some concrete feedback you received?

The feedback we received from editors generally fell into one of two categories: craft issues and marketing issues. In terms of craft issues, the novel had two main problems. The first problem was that the antagonist—Blanche—appears too late in the story. YWST has three point of view characters. The draft that we submitted to publishers was structured in three parts. The first ~75 pages were in Izzy’s point of view, the next ~150 pages alternated between Izzy, Blanche, and Taejong’s PoVs, and the final ~50 pages returned to Izzy’s point of view. Since Part 1 was solely in Izzy’s perspective, Blanche doesn’t physically appear in a scene until the 60-page mark when the novel turns into Act II. Up until this point, Blanche is working off-page in the background to disrupt Izzy and Taejong’s progress toward their goals. Even though, Blanche is indirectly creating obstacles to block their goals and create conflict, the tension in the first part of the novel is lax because the conflict is not overtly person vs. person; it’s person vs. an unknown entity.

Since Blanche is a vague force of antagonism before she appears on the page, the overall conflict is vague. Vague conflict causes lax tension and lax tension causes readers to stop reading. As a result, much of the feedback we received from editors said that the pacing of the novel was too slow. Pacing is best defined as the progress the protagonist makes toward their concrete goal. In effective stories, the antagonist places concrete obstacles in front of that goal and creates concrete consequences if the protagonist fails. Without Blanche’s physical presence on the page in Part 1, the obstacles and consequences she creates aren’t concrete enough to be effective. Now, with two years of hindsight since we went on submission, this craft issue seems so obvious to me, but I couldn’t see the forest for the trees in my revision process back then. Sometimes, we truly do need time away from a project to make it the strongest story it can be.

The second craft issue is more of a style problem. When I wrote the first draft of YWST, I was inspired by The Incendiaries by R.O. Kwon2, The Road by Cormac McCarthy, and stories in Claire Vaye Watkins’s Battleborn, and I chose not to use dialogue quotation marks in the novel. I was drawn to this stylistic choice for two reasons. The first was that I liked the “quieting” effect that omitting quotation marks had on the narrative. Kwon, McCarthy, and Watkins’s books all explore the impact of violence, both physical and psychological, on their protagonists. The absence of quotation marks complicates the tone of “loud” or high-risk scenes of violence, and I wanted to emulate that effect in my own book. I was also fond of the unreliability that the lack of quotation marks creates. I could manipulate the reliability of each narrator by blurring whether or not a line of dialogue was narration or a verbatim quote from a character.

In our last craft lesson, we broke down best practices for writing and studying effective dialogue. As a writer, I do think dialogue is one of my greatest strengths, but we received feedback that some editors didn’t think the dialogue was effective. It might be absolutely wild to conclude, and (so incredibly silly if true!), but I truly believe that omitting quotation marks played a significant role in some of the nos we received.

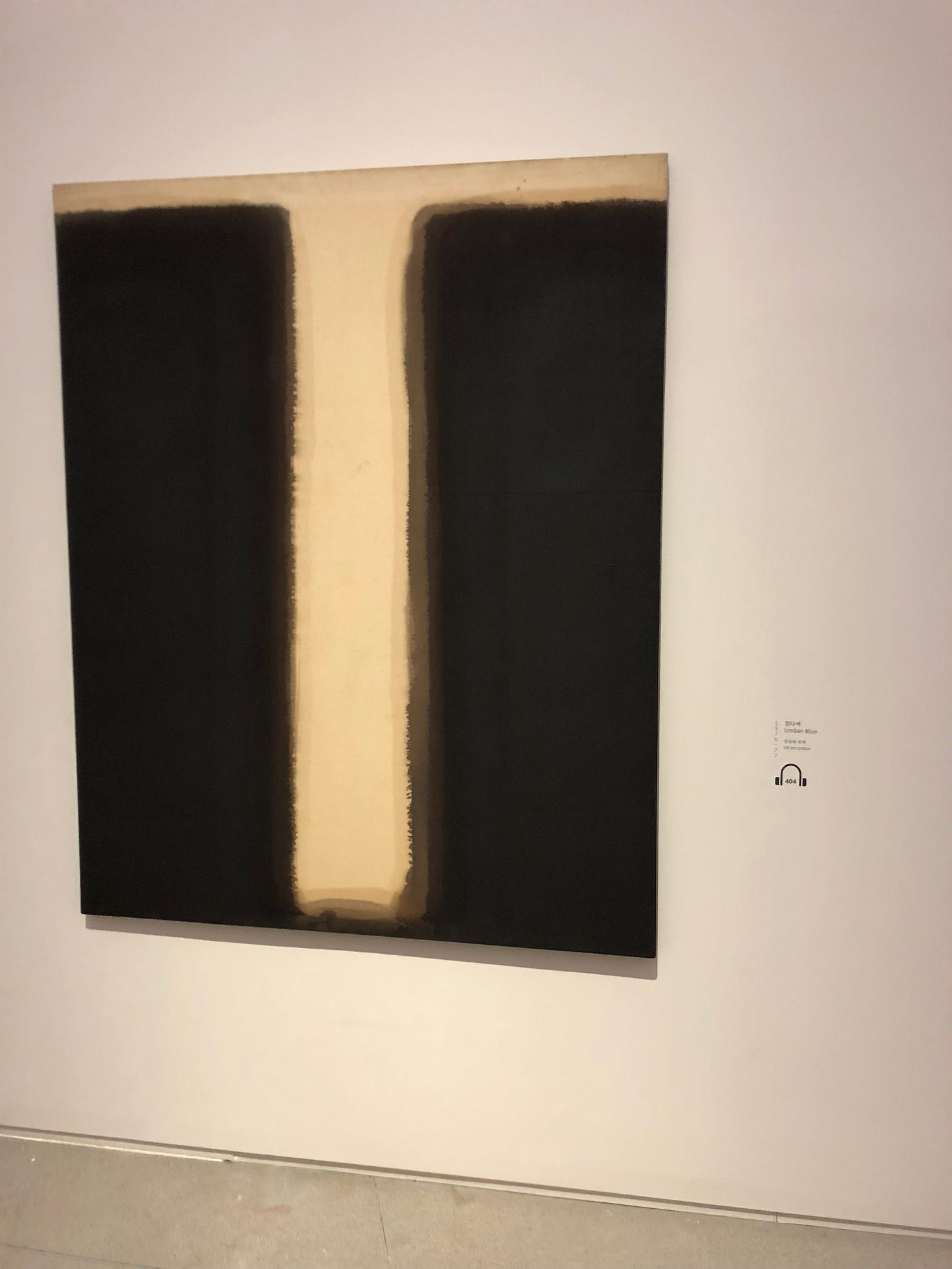

In addition to the craft issues, three marketing issues created challenges for YWST. The first is the book’s title. You Will Survive This is a bad title because (1) it’s too long, (2) out of the four words and 21 characters, only one word (survive) is a potential marketing keyword, and (3) the title’s keyword doesn’t immediately establish the book’s genre or exploration of immortality, folklore, or romance. Since I started this project in 2018, I’ve had a hard time titling the book. It’s original title was 천지문 (Cheonjimun), a portmanteau of the Korean words for heaven, earth, and gate, which was ultimately translated to English as The Gate of Heaven and Earth. This title comes from a series of paintings that play a significant role in the novel. You can read more about the paintings and original title here.

Needless to say, I always knew there would be marketing issues for using a Korean title for an English-language book, and I didn’t want to use the translation—The Gate of Heaven and Earth—because “heaven” has a very strong and specific connotation in the west. In the end, I settled on You Will Survive This because one of the characters says this near the climax of the novel. But now that I’ve sold a book (and had it re-titled by my publisher3), I better understand how a novel title impacts marketing. Books benefit from keyword-driven titles that immediately give a reader an idea of what the novel will be about. “Survive” as the sole keyword in the title could work for a novel about characters stranded on a desert island, but it doesn’t work for a novel about three people in a race to kill an immortal man.

The next marketing issue relates to the “relatability” of the novel’s protagonist. Although the book has three point of view characters, Izzy is very much the central protagonist. In the passes we received, a common comment was that some editors had a difficult time relating to Izzy as the protagonist. I’ve written before about my concerns on whether or not there’s a market for books about Black people in Korea. Now, realistically, I can’t solve this problem on the page without either (1) setting the novel in the US or (2) changing Izzy’s ethnicity. Since both of these changes would dramatically change every aspect of the book, I’m not willing to do either. But that means I should cater to the western market in other ways. Some of these ways include changing the title, revising the novel to have a more commercial pace, and modifying the comps in the pitch letter that accompanies the book’s submission.

That brings us to the third and final challenge for the book—it’s comps. As you know, comps are comparative titles that show industry stakeholders (agents, editors, etc.) that similar books to yours have already had commercial success. The goal of comps is to show these stakeholders that (1) there is an established market for your book, (2) that your book’s theme and style fits into this market, and (3) that there is precedent for publishers investing in books like the one you’ve written. For more on how to use comps while pitching your novel, check out our post, “How to Write a Query Letter.”

How to Write a Query Letter

Learning Objective: By the end of this post, you will know how to write and revise a query letter.

Now that I’m in the process of launching my debut novel, I’m realizing that there’s a difference between writing comps and marketing comps. A writing comp is the comp title writers use in a query letter to agents. These comps focus on establishing how the style and themes of your novel are similar to successful books in the same genre. Marketing comps, however, focus more on the book’s audience. When I queried Good People in 2019, I used comps that shared aspects of Good People's humor, style, and themes. When my agent and I submitted Good People to S&S for the revise and resubmit request that actually sold the book in 2024, we updated the comps because some of them had become too old in the five years since I queried. Then, last October, I met with my editor to discuss our next revision and the jacket copy for the book. When it came to marketing comps, he used completely different comps that I had never considered for the book before. Some of his comps were books I had already read and loved. Two of the books were novels I hadn’t read yet but instantly understood why he chose them. In general, his comps weren’t necessarily close matches in style or theme. Instead, they were matches in terms of audience, or—if we’re being really capitalistic about it—consumers. He laid out a marketing persona for Good People’s ideal reader and determined that this reader had purchased books by the comp authors he had listed.

Now, at a glance, these marketing comps might seem similar to the writing comps that go in a query, but I think there’s a key difference in the guiding question that helps a writer come up with their comps. When working on my query letter, I basically asked myself, “What books inspired Good People’s style and theme?” But while working on marketing comps for my book, my editor asked himself, “Who will buy Good People? And what books did these readers buy in the last five years?” The first question focuses on the art and writing—which is good, important and valid! The second question focuses on the book’s potential for commercial success and literary recognition. Having an audience-first approach to comps naturally turns your attention to books that were commercially successful with a specific demographic of readers. Marketing comps like these can help industry stakeholders (and consumers!) see the value of acquiring a book more effectively than writing-specific comps. Since Good People’s jacket copy isn’t finalized or public yet, I have to speak in abstractions. But once Good People is available for preorder, I’ll write a post with deep, in-the-weeds specifics about comps, marketing personas, and how the “sausage is made” for promoting books. In the meantime, as I work on my second book, I’m going to outline YWST’s ideal reader, figure out what books they bought in the last five years, and use those books as comps, especially since all three of my current comps are now too old to be effective.

Step 2: The Reasons for Resurrection

Once you’ve done a full autopsy on your book, it’s time to examine why you want to resurrect it. In my writing life, there have been projects I’ve toiled away at simply because of a sunk-cost fallacy. I’d justify this unproductive work to myself by saying, “I spent so much time on this book. I have to make it work.” Now, with years of distance from these projects, all I can do is look back, shake my head, and wish I had moved on from them sooner. That said, the next step in the process is to critically consider why you don’t want to give up on this dead book.

Here are five guiding questions to help you flesh out your reasons for returning to your book:

How did you come to write this book?

What was the seeding idea that inspired the book? What about this idea compelled you to actually sit down and write as opposed to other ideas you may have gotten over the years?

How long has it been since you’ve last worked on the book?

The goal of this question is to verify that you’ve had enough time away to see the book in a new light.

What else have you written since you stepped away from this project?

If you haven’t worked on anything else, that’s totally okay! It could be a strong reason to return to this project.

How is this project stealing your attention away from other things you could be writing now?

What are the strengths of this project, and how are they inspiring you to not give up quite yet?

The goal of this question is to ensure that you’re not abandoning a valid project because of a sunk-cost fallacy.

What are some of the changes you could make in this next revision?

For me, I feel compelled to return to YWST because it was part of my Fulbright project. In general, this book is a love letter to Korea, the place I spent most of my adult and professional life, so its characters and themes hold a special place in my heart. Now that I’ve had two years away from this project to process all of the baggage related to selling this book, I can see its objective strengths, and more importantly, I can see concrete steps I can take for revision. Since Part 1 is slow because it's only told from Izzy’s point of view, I’m going to restructure the novel to open with a Blanche chapter and then consistently alternate between the three point of view characters for each chapter. Now that I have a macroscopic editorial vision for this rewrite, I can work backwards to create weekly editorial goals for my next draft.

Step 3: The Means of Resurrection

Now, looking back at your book’s autopsy, it’s time to create a concrete revision plan. For this step, you only need to ask yourself one question: “What can I do on the page to resolve the challenges outlined in Step 1?”

If your book died for internal reasons, some of the revision plan may involve studying craft, experimenting with its execution in your book, or testing out new time management methods to better prioritize your writing life. If your book died for external industry reasons, it’s time to list out the craft or marketing issues and what you can do on the page to resolve them.

Here’s an example for YWST:

Craft Issue #1: The antagonist appears too late in the story.

Solutions: Restructure the novel.

Open the novel with a short chapter in the antagonist’s point of view.

Alternate consistently between the point of view characters for each chapter.

Craft Issue #2: There are no dialogue quotation marks.

Solution: Add quotation marks. A stylistic choice isn’t worth the risk if it’s alienating industry stakeholders.

Marketing Issue #1: Bad Title

Solution: Find a title that immediately establishes the book as a genre-blending novel about folklore and immortality.

Marketing Issue #2: Relatability for stories about Black people in Korea

Solutions: Instead of catering to this marketing issue, prioritize other changes that improve marketability.

Change the title.

Revise to create a more commercial storytelling pace.

Talk to my agent about including a pitch deck with market research on Black readers and Black K-drama watchers.

Marketing Issue #3: Wrong Comps

Solution: Use audience-facing comps instead of writer-facing comps in the submission packet.

If you’re interested in learning concrete steps for creating a comprehensive revision plan, check out our craft lesson, “How to Revise with Feedback.”

Recap: A Guide for Option Books and Novel Necromancy

When a writer signs a contract with a traditional publisher, the publisher typically gets first “dibs” on their next book-length work. This book is often called an “option book.”

Books die. Sometimes, they die because their writer loses interest. Other times, they die because agents or editors don’t show interest in publishing the book.

There are two types of comps: writing comps and marketing comps.

Writing comps focus on the interests of the book’s writer.

Marketing comps focus on the interests of the book’s audience.

Audience-first comps can more effectively establish a book’s marketability.

If you’re interested in reviving a dead book in revision, follow these three steps:

Step 1 – The Autopsy: Analyze why your book died in the first place by answering the three guiding questions above.

Step 2 – The Reasons for Resurrection: To avoid a sunk-cost fallacy, examine your reasons for returning to this book with the five guiding questions above.

Step 3 – The Means of Resurrection: Outline the steps you can take in revision to resolve the issues you found in Step 1.

Okay, so I lied in the subtitle of this post because nothing about this was brief. Thanks for sticking with me today! Let’s talk about your writing processes.

Have you ever revived a dead book? How do you know when it is time to move on from a writing project? How do you know when it’s time to dust a book off and work on it again? What helps you jump back into a project after time away?

Share your tips in the comments:

Until next time,

Kat

If you’re curious about what it takes to revise a book for submission to publishers, you can read an end-to-end process breakdown here.

This post includes affiliate links. I may receive a commission if you make a purchase through these links. Purchasing books through the Craft with Kat Bookshop supports the free writing resources I share here on Substack.

Good People’s original title was Lit by Burning. We changed it for marketing reasons that I’ll discuss closer to the book’s release.