Don’t Write What You Know

Writing Advice Remix with TRANSPLANTS author Daniel Tam-Claiborne

Have you ever been told to "write what you know" and still felt completely stuck? You're not alone! Welcome back to Writing Advice Remix, the interview series where we take well-intentioned but often unproductive writing advice and give it a much-needed makeover.

Today, I’m thrilled to welcome NEA Fellow Daniel Tam-Claiborne. Daniel is the author of Transplants1, a coming-of-age novel about race, love, and what it means to belong. I first met Daniel at an advisory board meeting for Off Assignment, a literary magazine about travel and the human experience across borders. Many of us at the meeting were American expats, and Daniel and I bonded over our time abroad in Asia. In today’s Writing Advice Remix, Daniel grapples with permission, what it means to “write what you know,” and what we owe to the communities we write about.

1. What’s the worst piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard? What problem is it supposed to solve? And why is this advice actually unproductive?

I think the idea that as writers we should “write what we know” gets bandied around a lot. On the surface, it’s not terrible advice. Writing from a worldview we already inhabit or from our own lived experience limits the amount of research that has to be done and reduces the considerable barriers we construct to putting pen to paper.

While I don’t think it’s bad advice per se, I believe it’s incomplete. Applied too literally and a writer could accidentally pigeonhole themselves and limit their potential. While I appreciate a good number of the first person-driven narrator-as-a-stand-in-for-the-author novels that we’ve seen proliferate over the last decade especially, I’m often left with a feeling of wanting more.

This was, after all, the case with my first book, What Never Leaves. Though it’s ostensibly fiction, it reads like thinly veiled memoir because the narrator’s experience so closely mirrors my own. It was an important book for me to write at the time—twenty-four and desperately trying to make sense of my two years living and working in rural China—but the most common piece of feedback I received from readers was that they wanted to know more about the other characters that populated this world. Who were they? What were their backgrounds? How did they feel about the events that were transpiring? At the time, I didn’t feel like I had the authority to write them fully—it wasn’t what I knew. It would take over ten years, an MFA, and countless start-and-stop attempts to re-visit the initial setting of What Never Leaves and write what would eventually become my debut novel, Transplants.

2. Now that you’ve written, revised, and published your book, how would you reframe that advice into something that’s actually helpful for writers?

Instead of strictly writing what you know, I would reframe the advice as writing what you want to know. Your curiosity as a writer is what sets you apart. Rather than shy away from it, let it guide the stories you gravitate towards. I strongly believe that every writer has stories that only they can write, though it doesn’t mean that those stories are, strictly speaking, known to those writers at the outset.

As you grow in your writing life, the easier it will be to discern what makes a good story and, importantly, what questions to ask. The further away a story is from what you know, the more effort is required to tell it well. I don’t say that as discouragement but rather pose it as a challenge. You know your story will be one you want to write because you’re enthusiastic and interested in the topic and characters. I’m not of the opinion that good writing is meant to flow effortlessly from your fingertips and abound with joy. Writing is almost always done, in my experience, with a healthy dose of misery. But the more you write what you want to know, the more you’re willing to jump through those hoops to do it.

3. What are three concrete steps a writer can take to incorporate this revised advice into their writing process?

One: stay open and curious about the world. There is still a remarkable amount of beauty and wonder out there even when it appears that our world at present more closely resembles a heaping trash fire.

Two: identify for yourself why you’re the right person to tell a particular story. Again, this is not meant to dissuade you, but rather to act as motivation for the long, often lonely period of excavation.

Three: do your research. Writing what you want to know means asking questions because the answers aren’t readily apparent. Do it often—of yourself, of your characters, of others who have walked in the shoes of those whose lives you’re exploring.

4. Let’s talk about Transplants. How did you integrate this advice into your own writing process?

Transplants is a coming-of-age story following two young women—one Chinese and one Chinese American—as they learn what it means to be their truest selves in a world that doesn’t know where either of them belong. It's an exploration of race, love, power, and freedom that reveals how—in spite of our divided times—even our fiercest differences may bring us closer than we can imagine.

Even after writing and publishing What Never Leaves, the experience of living in rural China never left me—as it were—and I knew that there were more stories from that experience that I wanted to tell. However, I also knew that I was sick of the mixed race Chinese American protagonist who was at the center of that first book. Instead, I was interested in looking at the peripheries, at the experiences of others who populated that world and who might better be suited to answer some of the lingering questions I had around power, love, and cultural expectations that preoccupied me during that time.

Liz and Lin, my two protagonists, came to me quite naturally as embodiments of the complex story I was interested in exploring around privilege, identity, and who gets to belong in the societies we’re born into. But as a male writer and a mixed race Chinese American, there was a lot about the experiences of these two female protagonists that was not immediately known to me. In order to delve into their stories and portray their trajectories with as much nuance and accuracy as I could, I conducted dozens of interviews, enlisted Asian American female first readers, and consulted many books and scholarly articles including Racial Melancholia, Racial Dissociation by David Eng and Shinhee Han; Racing Romance by Kumiko Nemoto; and Under Red Skies by Karoline Kan.

For me, U.S.-China relations is more than a headline; it’s in my blood. As someone who has had a foot in both countries, it felt paramount to me to tell a story that painted a human portrait at the heart of an increasingly contentious discourse often stripped of this essential anthropological dimension. Writing about Chinese in America and Americans in China with greater sensitivity, tolerance, and insight, especially at a time of unprecedented anti-Asian hate, is not only timely but urgent. Many people are questioning where “home” truly is. For immigrants, for the Chinese diaspora, for so many of us caught in between, that question feels more pressing than ever.

5. Looking beyond this specific piece of advice, what's the most important lesson you've learned about craft?

My high school creative writing teacher, Jon Kawano, who got this stubborn wannabe engineer to fall in love with writing told us to “turn on your lights.” Most ideas and concepts have already been expressed, better and more eloquently, by writers who have come before. The only way to still come up with fresh ideas is to keep our eyes and senses open—to notice and record those things that most people miss or take for granted. “As an adult,” he said, “it is an artist’s job to teach you to see as a child again.” He described our world as a wealth of things to be perceived and information to be processed. Our synapses are like a door of perception that shrinks with age until it becomes a narrow peep hole. As children, our gates are wide open, absorbing the flood of the world. He wanted us to preserve that precious time, to keep those doors open for as long as possible.

Daniel Tam-Claiborne is a multiracial writer, multimedia producer, and nonprofit director. His writing has appeared in Michigan Quarterly Review, Catapult, Literary Hub, Off Assignment, The Rumpus, HuffPost, and elsewhere. A 2022 National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellow, he has also received support from the U.S. Fulbright Program, Kundiman, Sewanee Writers’ Conference, the New York State Summer Writers Institute, and others. Daniel holds degrees from Oberlin College, Yale University, and the MFA Program for Writers at Warren Wilson College. His debut novel, Transplants, was a finalist for the 2023 PEN/Bellwether Prize for Socially Engaged Fiction and is now out with Regalo Press (Simon & Schuster).

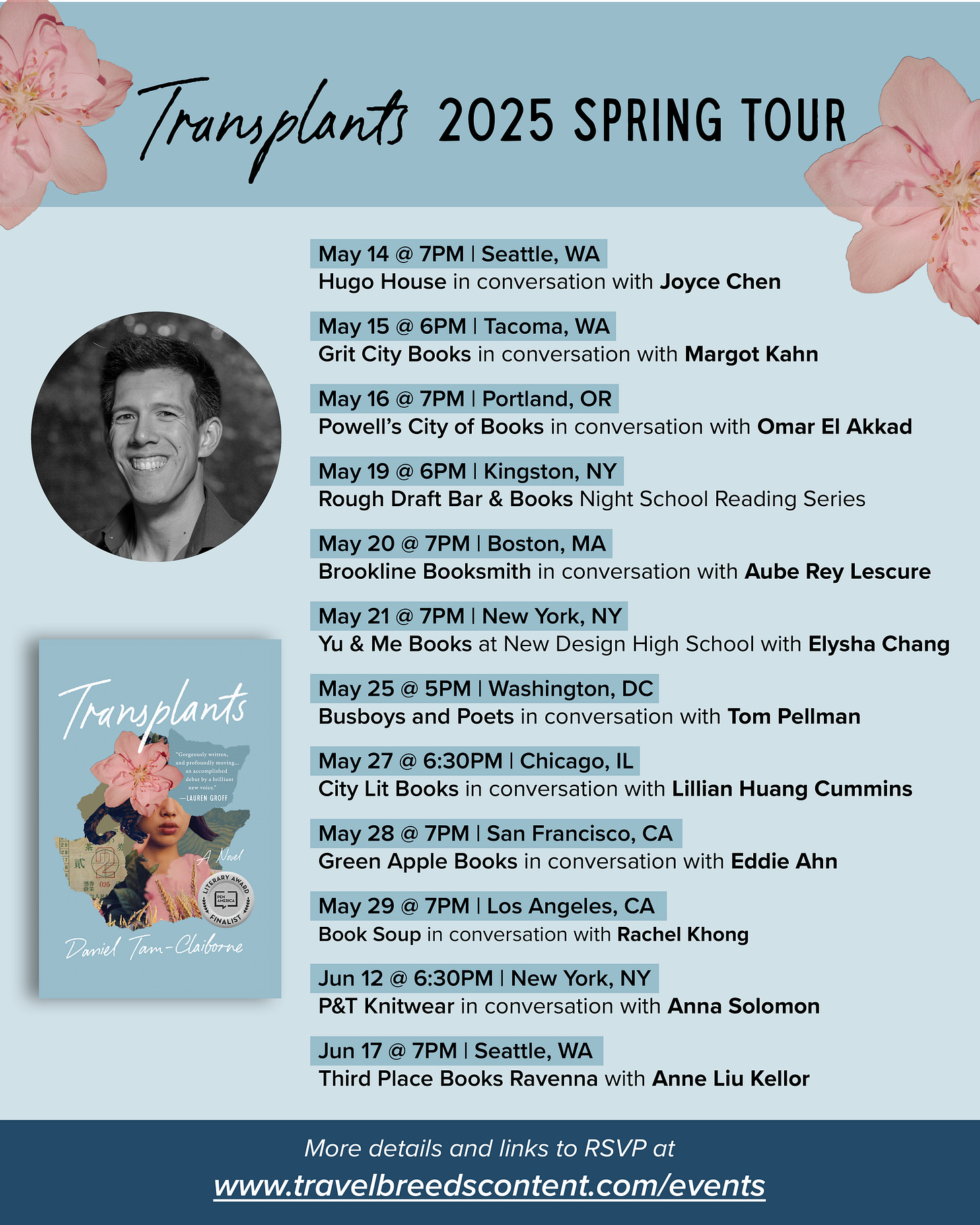

Where to Find Daniel Tam-Claiborne:

What are your thoughts on the ever-present “write what you know” advice? Let’s talk about bad writing advice in the comments:

Until next time,

Kat

This post includes affiliate links. I may receive a commission if you make a purchase through these links. Purchasing books through the Craft with Kat Bookshop supports the free writing resources I share here on Substack.

Great advice. I fret about autobiographical elements in my novel-in-progress. This might help me reframe things.

I love this advice to “write what you WANT to know.” How beautiful, smart, and inspiring—thank you!