How to Publish a Novel with a Big 5 Publisher (Part 1)

Practical Resources for Every Stage of the Writing Process

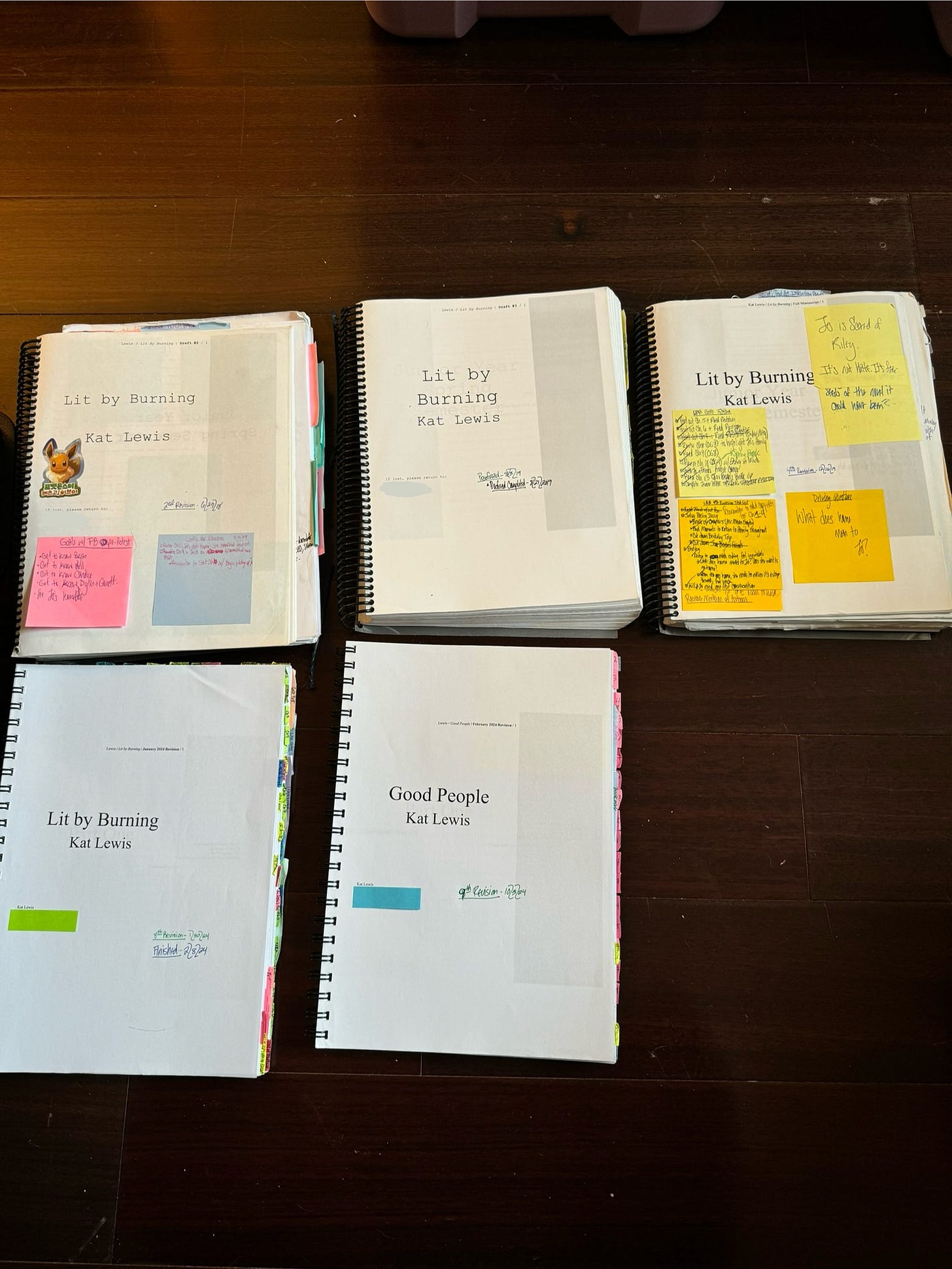

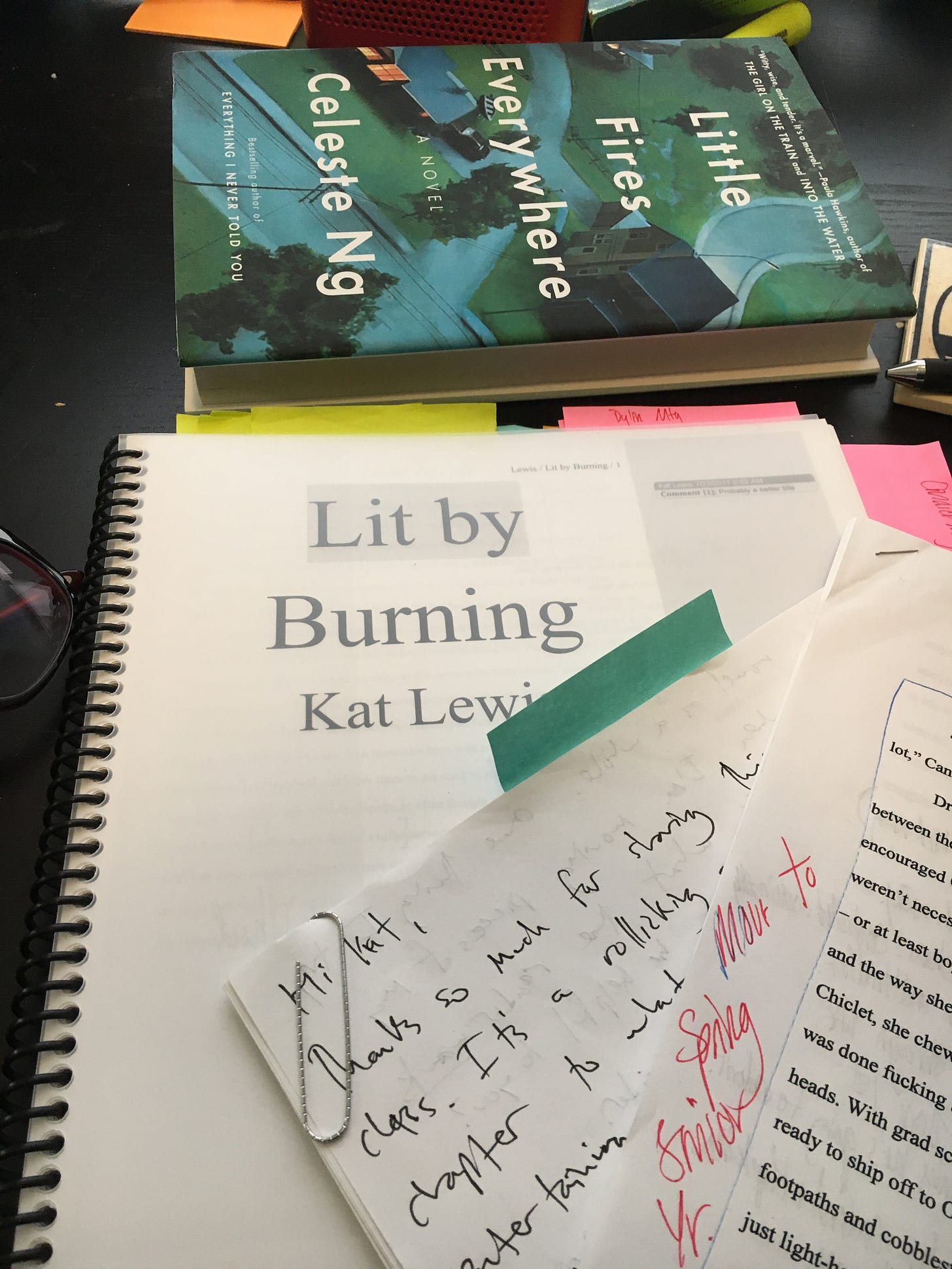

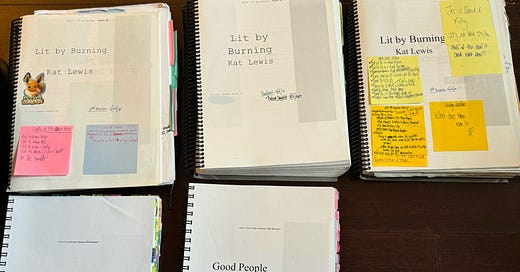

Last April, I sold my debut novel, Good People, to Simon & Schuster. Five months later, I moved back to the US after spending the last few years working as a video game writer in South Korea. While unpacking my things in the US, I rediscovered several drafts of Good People that I had written before S&S acquired the novel. Now, as I’m wrapping up what might be my book’s final revision before it moves onto copy edits, I’ve been looking back at the nine drafts I’ve written. Each of these drafts taught me a new strategy or technique that ultimately brought me closer to achieving this lifelong goal of selling a book to a Big Five publisher.

My journey to publication has been taxing for a myriad of reasons, but those reasons mostly boil down to one main challenge: the process of writing and revising a novel is often vague and abstract. To overcome this challenge, I’m launching a series of posts that will demystify every stage of the novel writing process. Whether you’re working on your first draft, preparing to query agents, or revising to meet your delivery and acceptance deadline with a traditional publisher, these posts will (1) identify common problems for every stage in the process and (2) offer concrete steps you can take to solve these problems in your writing life. Today, we’re starting with first draft problems and potential solutions. As always, take what’s useful to you and your writing life (if anything at all) and leave what’s not behind.

Good People’s Pitch for Context

Jo Tope’s birth mother left her in a high chair in the neighbor’s house and never came back. This is how the Topes, a Black family of four, adopted a white baby.

Good People follows Jo Tope, a habitually drunk college student who desperately wants to become white. Growing up with her identity split between the Black family that raised her and the white schools she attended, Jo always thought that college would be her chance to escape her past and fully embrace whiteness. Now, a junior at Johns Hopkins University, she pursues a Rhodes Scholarship, believing that a graduate degree from Oxford is her path to becoming a “regular white person.” But when her alcoholic tendencies threaten her personal relationships and her chances at the Rhodes, Jo must learn that whiteness will not save her before she loses her academic future and the people who matter most.

First Drafts

Good People’s First Draft

Although Good People began as a series of short stories that I wrote in 2015, I didn’t sit down with the intention to write a novel until the summer of 2017. At the time, I had just quit my job in publishing after getting accepted into the MFA program at the University of San Francisco. I had saved up just enough money to survive the summer without a job, and that meant that I had three months of “writing full-time.” My goal was simple: finish the first draft of my novel before I started grad school in August.

While working on this draft, I struggled with creating an overarching narrative for the novel. This struggle was largely rooted in the fact that Jo’s story began within the container of a short story, not a novel. Before the novel had found its external plot of Jo’s pursuit of the Rhodes, I had written six short stories about pivotal moments in Jo’s life as an unhinged college student. I had planned for these six stories to function as tent poles that would hold up the novel. All I had to do was fill in the time gaps between these milestone stories with notable events from Jo’s life. Easy, right?

Wrong.

First Draft Problems

During the first year of my MFA program, I learned two crucial things about narrative tension and the key genre differences between a short story and a novel. In Lewis Buzbee’s novel workshop, he taught our class that short stories explore the possibility of change whereas a novel explores the consequence of change. Alan Watt defines this change in The 90-day Novel by claiming that characters do not have problems; they have unsolvable dilemmas. Since the dilemmas cannot be resolved, the character must transform through a shift in their perception in order to survive the story. In other words, a short story often ends before the protagonist has to radically transform to literally or metaphorically survive the consequences of the story. But in an effective novel the protagonist typically must transform by the end of the story, or they will die a literal or metaphorical death on the page.

Since the first draft of my novel was written to connect six short stories, Jo constantly teetered on the precipice of change, but never actually transformed. As a result, the tension throughout the first draft of the novel was lax because Jo did not transform, and the narrative did not punish her for her failure to transform with the consequence of a literal or metaphorical death.

This brings us to the second most important thing I learned in my first year—narrative tension. In our craft lesson on tension and consequences, we used the following definition for tension:

Tension: The sense of anxiety that conflict creates for the protagonist, and in turn, the reader. This anxiety is what compels the protagonist to act until they accomplish their goal and the reader to keep reading until they finish the story.

During my first semester, I workshopped ~50 pages of Good People in Michael David Lukas’s fiction workshop. In class, he taught us that there are two types of tension—acute tension and chronic tension. When effective, the acute tension in a novel answers the following questions for any given scene or chapter:

What is the protagonist’s short-term goal?

What concrete obstacle is preventing them from achieving that goal?

What bad thing will happen in this scene or chapter if the character fails to accomplish that goal?

How does the protagonist need to change in this scene or chapter in order to achieve their goal?

Why are they so afraid to change?

Chronic tension, on the other hand, focuses on five big-picture questions for a novel:

What is the long-term goal the protagonist must achieve by the end of the novel?

What is the main, concrete obstacle preventing them from achieving this goal?

What bad thing will happen if they fail to accomplish this goal by the end of the novel?

How does the protagonist need to change before the end of the novel in order to accomplish their goal?

Why are they so terrified of changing in this way?

Since the first draft of Good People was essentially six core short stories that were connected by what were effectively more short stories, this draft had acute tension at the chapter level, but no chronic tension at the macro level. Without chronic tension, the individual chapters did not connect into a single, cohesive novel-length narrative. This flaw created a critical problem for my first draft: why should a reader read the next chapter if this chapter already had a complete narrative? In the end, since each chapter had a complete narrative and Jo did not perceivably change in any of those narratives, there was no chronic tension compelling the reader to read chapter to chapter.

While this problem is derived from the novel’s origin as short stories, it’s also amplified by the fact that I was a discovery writer. I did no planning whatsoever before writing my first draft. I only had a vague idea of where each of the original short stories would appear in the novel. For a lot of writers, discovery writing is an effective way to stay motivated and get that first draft written. This was certainly the case for me. But now, looking back at the nine years and nine novel drafts it took to get me from ideation to a signed contract, I can see that discovery writing didn’t serve my ultimate goal of selling a novel to a Big Five publisher.

Discovery writing didn’t help me in the long run because this method meant that I was writing a meandering draft with a meandering plot. All of this is just a painfully polite way to say that my novel’s first draft had no chronic tension, no plot at all to speak of. If your goal is to sell your novel to a major publisher, the hard truth is that your book needs plot—especially if you’re trying to break into the industry as a debut writer. For more on the reasons why your novel needs plot, check out

’s list of eight things your novel must have to enjoy a fighting chance with Big 5 editors in 2025. As a whole, I didn’t write my first draft with a lot of concrete intention, and this lack of intention is one of the reasons why the novel failed to sell the first time we went on sub in 2020.If you’re ready to write with intention and inject concrete plot and chronic tension into your novel, here are some practical craft resources that might help you on your writing journey.

First Draft Resources

First drafts often lack tension—a reason for the reader to keep reading—because they’re missing one or more of these three key elements:

A concrete external goal for the protagonist to win, stop, escape, or retrieve

An obstacle to block their goal and create conflict

A clear, inevitable consequence if they fail at this goal

Here are three resources that provide concrete steps to creating goals, obstacles, and consequences that will make your novel appeal to Big Five publishers.

1. Creating External Goals

The guiding questions in this craft lesson will crack open your character’s motivations. By deepening your understanding of your character’s external goals and internal needs, you’ll be able to develop a more unique plot and, in turn, a more marketable premise for Big Five publishers to consider.

The questions in this lesson helped me identify and overcome my greatest weakness as a writer. For so many years while working on Good People, I used strong scene craft and effective acute tension to conceal the fatal flaw of my novel. While working on the first six (yes, six!!!) drafts of my novel, I truly could not answer this basic question: what does Jo want? Since I couldn’t answer this question, my novel had no plot. Since my novel had no plot, I couldn’t sell it to a Big Five publisher. Even though I finished Good People’s first draft in 2017, I wasn’t able to sell it to a major publisher until 2024 when I revised to add concrete character goals to the novel.

Whether you’re writing your first draft or your tenth, the guiding questions in this craft lesson will walk you through concrete steps you can take as a writer to give your protagonist tension-inducing external goals.

The Four Elements of Character Goals

Learning Objective: By the end of this post, you will know how to develop your character’s goals with four guiding questions.

2. Obstacles and Conflict

Tension is what keeps readers reading and tempts editors into making an offer on your book. Tension needs concrete conflict to be effective, and conflict arises when you set an obstacle in front of your protagonist’s goal. This obstacle is most effective for the western publishing market if it's a person. In this craft lesson, you’ll discover three strategies for creating compelling antagonists that will give your novel a propulsive plot.

A Story Is Only as Good as Its Bad Guy

Learning Objective: By the end of this post, you will know how to develop your story’s ordinary world, inciting incident, and antagonist to create compelling conflict.

3. Well, If It Isn’t The Consequences of My Actions

In Buzbee’s workshop, he also taught us that a story starts on the day the protagonist begins their march to their inevitable end. The protagonist’s journey toward their inevitable end is their march toward transformation (or their failure to transform). Effective stories put pressure on their protagonist to transform by creating concrete and painful consequences for staying the same. This series of posts provide over forty guiding questions that will help you develop consequences for your character’s actions. These consequences will have your characters (and your readers!) looking like Surprised Pikachu.

Act I: Setting a Trap for your Protagonist

Learning Objective: By the end of this post, you will know how to use three key beats to create conflict and consequences at the beginning of your story.

What are some of your strengths as a writer? What writing resources helped you refine those strengths? Outside of plot, what are some other things that Big Five publishers look for in a novel?

Let’s talk all things publishing and writing craft in the comments:

Until next time,

Kat

Since some people mentioned how helpful it was to see a concise novel pitch in this post, I thought I’d share our post on pitch writing, “How to Write a Query Letter”: https://open.substack.com/pub/katjolewis/p/how-to-write-a-query-letter?r=1nxyt&utm_medium=ios

This post contains a step-by-step guide on how to write a query letter and pitches like the one included in this post. Our query letter lesson also contains the first draft of the query I wrote for GOOD PEOPLE, the final draft that got me my agent, and a revised draft of how I’d write the query letter now with 5+ years of hindsight and a book deal.

If this query letter post is helpful to your process, please let me know!

Thank you for your generosity and specificity in your post. What a gift!