How to Revise a Short Story with an Outline

A Guide to Using Greek Dramatic Structure in Revision

Last week, I shared the published draft of “Eat You Whole,” a short story about a Black ex-pat in Seoul who would do anything to avoid moving back to the US. I was on the fence about reprinting this story on Substack for a few reasons. For the most part, I didn’t want to share this piece because I had written the first draft in March 2020. At the time, outlining story structure wasn’t a serious part of my writing process, and now with three years of hindsight, there are a lot of narrative decisions in “Eat You Whole” that I regret. Even though I cringed when I reread the story, I ultimately decided to share it because I thought it would be a great opportunity to demonstrate how to use Greek Dramatic Structure (GDS) to revise a complete story draft.

To demonstrate how to use the GDS map as a revision tool, this week’s post will be structured around two outlines:

A reverse outline of “Eat You Whole” that analyzes the story’s strengths and the places where it could be even stronger

A revised outline of the story that would guide a rewrite

Before we continue, I want to say that I’m grateful to the contest and publication that gave this story a home. All of my regrets about this piece are wholly personal. I never reread a story after it’s published, and I’m likely only feeling some kind of way about it because I had to reread “Eat You Whole” to write these posts.

As you read this post, take anything that helps you and your writing life and leave everything that doesn’t behind. Also, a quick spoiler alert for the movie, Parasite. The Midpoint section of this post has a very small spoiler for Parasite.

How to Revise with a Reverse Outline

Before I fully integrated outlining into my writing process, I wrote my first drafts as a discovery writer and only used an outline to structure a revision. To do this, I would follow a four-step process:

Write a complete first draft with a rough premise

Select an outline structure

Reread the story and complete the outline

Note the story’s strengths and spots for revision

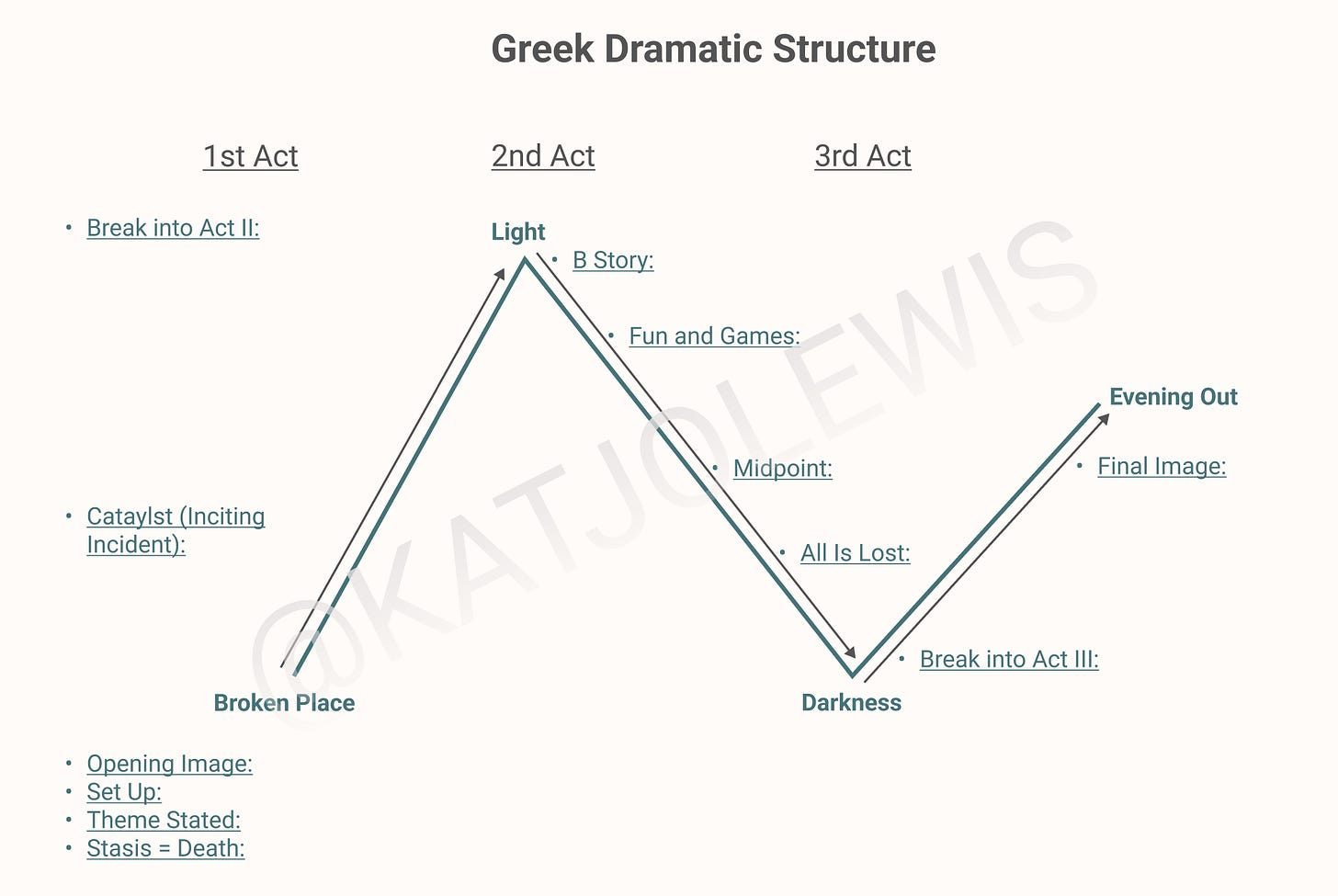

For today’s outline structure, we’ll be using the GDS map from our first craft lesson. In that lesson, we introduced two GDS maps. The first is a general map with a list of guiding questions that will give you an overview of your story’s plot. The second is a map that combines Greek Dramatic Structure with 12 of the Save the Cat story beats. If you’re a prose writer, I recommend checking out Save the Cat Writes a Novel by Jessica Brody if you haven’t already.

Today, we’re going to use the second Save the Cat GDS map. When I do this exercise after completing a draft of a story, I keep my GDS map brief with the intention of seeing the story’s big-picture structure.

Here’s how I used the Save the Cat beats to understand my story’s strengths and what needs to be revised.

Act I

Opening Image

Definition

The opening image is the first sensory experience a story gives its reader.

Reverse Outline

The story opens with a visual description of the bar-filled alleys of Sinchon.

Revised Outline

The imagery is effective and serves its purpose of establishing Seoul as the setting. I would keep the opening the same in revision.

Set Up

Definition

The set up is a beat that establishes four things about the protagonist:

Their Broken Place

Their Ordinary World

Their initial external goal

A question about their internal struggle

Reverse Outline

Honey is broke but terrified of moving back to the US. She needs a job to stay in Korea. The set up is effective because it establishes:

Honey’s Broken Place

She’s broke but cannot under any circumstances move back to her home country.

Honey’s Ordinary World

She’s a grad student living abroad.

Honey’s Concrete External Goal

She wants to get a job in order to survive the semester.

A question about her internal struggle

Why does she feel unsafe in America?

Revised Outline

Nothing to revise here. This beat in the story effectively sets up Honey’s problem and how she wants to solve it.

Theme Stated

Definition

Effective stories are about transformation. In western storytelling, the protagonist often needs to transform by learning a lesson in order to literally or metaphorically survive the story. The theme stated beat is when the lesson that the protagonist needs to learn is established. This lesson is often related to their internal need.

If this concept of transformation resonates with your writing philosophy, I recommend checking out The 90 Day Novel by Alan Watt.

Reverse Outline

Here we will find the first problem in this story. There is no theme stated beat. Toward the end of the story, there’s a paragraph about home and what it means to Honey now that she’s lost her family and her attachment to her home country. The concept of home is an effective, universal theme, but it’s explored too late in the story.

Revised Outline

If I were to revise this story, I would specifically establish two crucial details about Honey in Act I. The first is that she has lost America as her home. The second is that this loss has forced her to form a detrimental misbelief about home. In order to metaphorically survive this story, Honey would then have to transform through a shift in her perspective of what home means.

Inciting Incident

Definition

The inciting incident is the moment that forces the protagonist to begin their journey toward their goal.

Reverse Outline

The inciting incident is another point for revision in this story. As it stands now, the inciting incident is when Jia hires Honey to be a server at the restaurant. Now that Honey has accomplished her initial goal of finding a job, her next external goal is unclear. Her goal is unclear partially because the theme is not fully rendered in this first act.

Revised Outline

If Honey’s misbelief about home motivated her to win, stop, escape, or retrieve something in relation to Jia, then this inciting incident would be more effective. In revision, I would make the consequence of the inciting incident force Honey to pursue a concrete goal in order to get something she wanted from Jia.

There’s a seed of this conflict (desire vs. obstacle) when the narrator says:

As [Honey] walked home, she thought about Sajangnim chewing her half [of the gum stick] on her side of the city and how—like a craving, like a cat locked out of a room—she wanted to see Sajangnim’s face.

In revision, I would bring this simple goal to the foreground by giving Jia a specific reason for her not to show Honey her face. Maybe she was hungover and wearing sunglasses throughout their shift. Maybe she had been crying recently and her eyes were puffy. Whatever the reason, their conversation after Honey’s first shift would have more tension because they want opposite, concrete things from each other.

Break Into Act II

Definition

The Turn Into Act II is often accompanied by a life-changing moment that leaves the protagonist shocked or surprised. This beat is most effective if the protagonist’s external goal for the rest of the story becomes crystal clear in this moment.

Reverse Outline

In the story now, the Break into II happens in this paragraph:

Honey’s urge to pick at her nails, to tamp down every inky thing she had ever felt for the convenience of others waned. With the bullshit of pretense lifted, Honey sat up straight on her stool. When she looked at Sajangnim again, Honey understood that it wasn’t sadness that simmered in Sajangnim’s eyes, but the fatigue of experience.

While Honey is effectively surprised that she has a deep emotional connection with Jia, this moment is too subtle because her external goal has been unclear since she got the job. As a result, the story spins its wheels in the first act.

Revised Outline

In revision, I would actually make the current midpoint of the story (the moment where Honey discovers that Jia is an alcoholic) the Turn into Act II beat. Following this beat, Honey’s concrete, external goal would be to stop Jia from being/feeling alone. Honey would pursue this goal because she misbelieves that helping this woman will simulate a sense of home for her.

Act II

B Story

Definition

At the beginning of Act II, western stories often cut away from their main plot to a subplot. A subplot (or B Story) is a secondary storyline that is connected to the central story through a character’s relationships or external goals.

Reverse Outline

As this story stands now, there is no B Story beat. Short stories often do not have space for a fully realized B Story, but “Eat You Whole” is an example of a short story that would benefit from one.

Revised Outline

In revision, I would use the B Story beat to remind the reader that Honey is on a scholarship and must keep up her grades in order to stay in Korea and avoid her fear of moving back to America. Since this is a short story, I would create the B Story beat in just a couple of sentences by making Honey’s scene objective to study and Jia’s scene objective to take her out drinking. Jia would “win” the scene by successfully convincing Honey to stop studying and go out.

We’ll talk about subplots in depth in our next craft lesson.

Fun and Games

Definition

The Fun and Games section of the story is often described as “the stuff we see in movie trailers.” Parasite is about a family that cons a wealthy family by becoming their help. Most of the trailer shows moments where the protagonist, Kiwoo, takes actions to ingrain himself and his family more and more into the lives of the Parks.

Reverse Outline

In last week’s post, I shared this logline to introduce the story:

“Eat You Whole” is a short story that follows Honey Evans, a Black ex-pat in Seoul who will do anything to avoid moving back to America, but her relationship with her peculiar boss jeopardizes her chances of staying in Korea.

The Fun and Games in “Eat You Whole” is this paragraph of compressed narration that reveals how Honey and Jia bond after work.

Alone in the restaurant with Sajangnim, Honey shared parts of herself too, and this sharing made the grief in her chest shrink until it had the significance of a yawn. Honey worked at Jia’s House three nights a week, and this was how she spent the quiet hours of the night at the end of her shifts—getting shitfaced with Sajangnim. These nights, in between drinking games, they traded private stories with each other as if Sajangnim wasn’t Honey’s boss, as if they weren’t strangers, as if they had never been strangers. It was in this way that this woman stopped being Honey’s boss—the sajangnim of Jia’s House—and became simply Jia, a companion.

Revised Outline

While the paragraph above establishes their relationship well, in revision, I would use this compressed narration to demonstrate how Honey and Jia’s relationship becomes more and more codependent. This beat would occur after the new Turn Into Act II that would force Honey to pursue her overarching goal of comforting Jia no matter what.

Midpoint

Definition

The Midpoint is the second, big turning point in the story. Since the Turn Into Act II, the protagonist has been actively pursuing a goal. But due to their fears or misbeliefs, they’re likely going about things in the wrong way. Since the protagonist has not yet transformed to survive the story, they typically experience a false victory or a false defeat around the 50% mark of the story.

Even in quiet stories like “Eat You Whole,” the midpoint is a plot twist that once again changes the protagonist’s life as they know it. This is the moment in Parasite when the Parks are out of town, Kiwoo’s family is living it up in the Parks’s mansion (false victory), but then the former housekeeper rings the doorbell, and Kiwoo discovers what’s in the basement. Midpoints work best when the protagonist's original plan for action (their goal following the Turn Into Act II) is rendered completely and utterly useless.

Midpoints are my favorite plot point to outline. We’ll do an in-depth craft lesson on midpoints soon. If you want to learn more about midpoints now, check out this video from Abbie Emmons.

In the meantime, I’d love to hear about midpoints you’ve seen in stories. What’s a story you love that has a fantastic midpoint?

Reverse Outline

The midpoint that changes Honey’s new life as she knows it is the discovery of Jia’s drinking problem. While this moment has the ingredients to be an effective midpoint, it doesn’t stick the landing because Honey has been a passive protagonist for the first half of the story. A protagonist becomes passive when they do not have a clear, concrete goal and a specific obstacle (usually a person!) that’s in their way. As a result, Honey has no plan to throw out the window and no reason to scramble to create a new goal that raises the stakes and brings her closer to her necessary transformation. Creating new consequences for actions is how we raise the stakes of our story. My main goal with revising the midpoint would be to create an unexpected consequence for Honey’s pursuit of her external goal.

Revised Outline

All that said, in revision, I would once again make this discovery about Jia the Turn Into Act II. To create a more effective midpoint, I would move up the All Is Lost beat (Honey losing her scholarship) and make this beat the midpoint. Up until this moment in the revised story, Honey’s goal would have been comforting Jia at any cost, but her pursuit of that goal has now created a new consequence that threatens Honey’s visa status and her ability to avoid her fear of returning to the US. As a result, Honey would then have to come up with a new plan (read: external goal) to solve the problems related to both Jia and her scholarship. The story would be even more effective if there were a crisis decision that forced Honey to choose between Jia and her scholarship. It’d also be effective if this crisis decision represented Honey’s success (or maybe even failed!) transformation to survive the story.

All Is Lost

Definition

The All Is Lost beat is the low point of Act II. The protagonist has now fallen into the darkness outlined in the GDS map. In this moment, they are the furthest they will ever be from their external goal and necessary transformation. Now, they must transform or else they will, without a doubt, die a literal or metaphorical death.

Reverse Outline

Honey’s All Is Lost beat is when she receives the academic probation notice on the subway. In theory, this moment is effective because there is what Blake Snyder calls “a whiff of death.” In this story, the stakes aren’t literally life or death, but returning to America would be an emotional death for Honey. If Honey does not change, she will have to move back to the US, and her spirit will die the second she sets foot on the plane.

But the problem with “Eat You Whole” is that since Act I doesn’t effectively establish Honey’s goals, the theme of her story (home), and her misbelief about that theme, the reader is not as attached to Honey’s fear of death (going back to the US) as they could be. As a result, the story meanders and feels a bit random until we get to this moment. All of that randomness limits the audience's experience of Honey’s loss. If the reader’s investment in this loss is limited, then the stakes will feel too low.

Revised Outline

At this point in the revised outline, we’re coming out of the midpoint set piece where Honey discovers she’s on academic probation. For the All Is Lost beat, I would move up the scene where Jia passes out in the cab. As Honey carries Jia into her apartment, I would add compressed narration that emphasizes that this image of Honey carrying her drunken boss to her house that doesn’t feel like a home is rock bottom. As Honey puts Jia to bed, the whiff of death would be Honey’s realization that Jia will be the reason she has to go back to America.

Act III

Break Into Act III

Definition

Following the Turn Into II and the Midpoint, the Break Into Act III is the third most important beat in three-act structure. Similar to the Turn Into II, the protagonist experiences another life-changing surprise that revolutionizes their external goal. At this point in the story, the protagonist has shifted their perspective, discarded their misbelief, and now must take action that is aligned with their new, transformed worldview.

Reverse Outline

Since the story doesn’t establish its theme or Honey’s misbelief in Act I, the Break Into III isn’t very effective. There’s a surprise and realization that happens in this paragraph as Honey and Jia fall asleep in the dark:

Honey said nothing—only stroked Jia’s hair with her hand. She had so many questions for this person lying in bed with her, but she didn’t fault Jia for being the way she was; she didn’t even want answers as justifications. No, what she wanted was to know Jia because to Honey, to be known, to be seen, was a panacea for so many ailments of the mind. For this reason, she wondered who Jia was fighting with on the phone. Was it her brother? Her father? Why did her father kick her out all those years ago? These questions turned Honey to her own life: what would her own family look like had her father stayed, had her mom not passed away? What would home look like for her? Home. Honey hadn’t felt home since she was nineteen, since she put her mother in the ground. This was how she so easily returned to Korea again and again, how she accepted with sufferance the ruin of the place she had grown up in, a place that was riddled with racism like a contagion left uncontained, how she could lay in bed with this person lightly snoring in her arms, and strangely be glad of the loss that had brought them together. Yes, she was glad of the fact that here, in this foreign place made familiar and domestic, she saw, now, stretched out before her, the possibility of a new home, of a found family in Jia’s House, in Jia herself. Yes, Honey would find a way to keep her scholarship and keep Jia out of the hell in her head. Better to be eaten than to be alone . . .

One of my biggest frustrations with this story now is that there is so much potential for it. This paragraph does a lot of compelling character work, and I’m happy with the line-to-line writing here, but I did my writing a disservice because I did not set up this realization in Act I by establishing home as the theme of the story with Honey’s misbelief.

Revised Outline

In revision, I’d make the Break Into III the moment where Jia says to Honey, “I’ll eat you whole, you know . . . It’s the hell in my head. That’s why I’m like this. I’m sorry I’m like this.” This beat would surprise Honey because she was just at rock bottom carrying Jia in the hallway and considering breaking ties with her. But when Jia says, “I’ll eat you whole,” this moment surprises Honey because Jia demonstrates a level of self-awareness that (1) gives Honey hope for change and (2) precipitates Honey’s commitment to Jia even though she knows somewhere deep down that Jia will destroy them both. Ultimately, I think if I were to revise this story, I would make it a story about a failed transformation. Since Honey cannot prioritize herself and breakaway from this toxic, codependent relationship, she will ultimately die a metaphorical death because she misbelieves that this dysfunction is what home is and refuses to learn otherwise.

Final Image

Definition

The final image is the last sensory experience that a story offers its reader. The tone of this image often mirrors the tone of the ending.

Reverse Outline

The final image of the story is a very domestic description of Jia looking out the window and drinking coffee. The sight of Jia gives Honey a sense of home.

Revised Outline

Since I’m interested in making this story a failed transformation, I would keep the components of the final scene (the coffee, the bedhead, their simulated home together) the same, but I would tweak the tone and diction to emphasize the denial on Honey’s part that Jia won’t eat her whole.

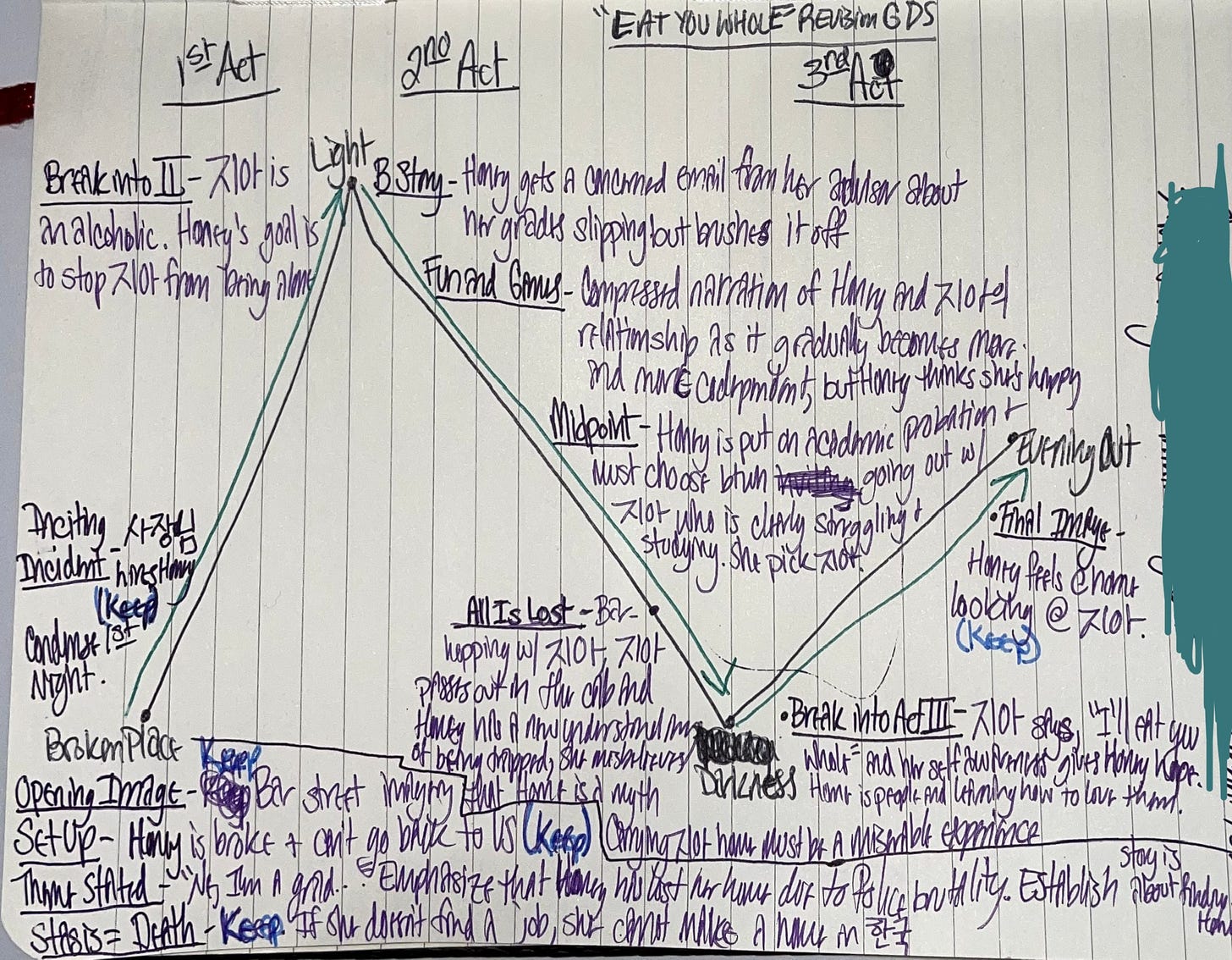

In terms of the revised outline’s GDS Map, here’s how it looks on the page:

What do you think of outlines as a revision tactic? Would you prefer to use an outline before or after writing your first draft? What other approaches do you use for revision? Let’s talk about them in the comments.

Next week, we’ll be continuing our Three-Act Structure breakdown with a craft lesson on how to structure subplots at the start of Act II. After that, our next AMA comes out June 25th. Drop your questions in the comments below.

See you next week!

- Kat

Thank you so much for sharing this! I enjoyed reading the story last week, but your reflections about how to take it further are so insightful. While I’ve made outlines for short stories before, I often feel like they focus on causality but not character transformation, and I’ve never used GDS to outline a story. I’m excited to give it a try this week!

I definitely prefer creating an outline first. I always get off track, though, and end up tweaking the outline to (Blake Snyder's words) straighten the spine of the story. I enjoyed Eat You Whole on first reading, even knowing that Honey's dream was doomed--that she would have a lot of heavy lifting ahead in a relationship with an alcoholic. Your suggested revisions would strengthen the story. Thanks for going through it--I learned a lot about structure from your analysis.